|

The water wheel on la Zanja Madre: Part 1  from Olmstead, 1910, after Stevenson, 1876 from Olmstead, 1910, after Stevenson, 1876 Not everyone is aware that there was a water wheel on la Zanja Madre. La Zanja Madre was the ditch that brought water from the Los Angeles River to downtown Los Angeles for more than 125 years. The first zanja was dug almost immetiately after the founding of the pueblo in 1781 because Los Angeles was initially a farming community; agriculture requires a significant amount of water and Los Angeles has a very dry climate.. Eventually, responsibility for the zanja fell to a person known as the zanjero, who was charged with keeping the zanja clear of grasses, obstructions, and dead animals (a lovely image, right? But it's true ...). The zanjero was a public official, responsible for issuing permits to use water from the zanja and collecting use fees from water users. He was paid a salary out of municipal funds. There seems to be a compulsion today on the part of some to refer to la zanja madre as 'the Mother Ditch', but that latter term is simply a literal translation of la zanja madre from the Spanish. Rest assured that no one in early Los Angeles ever called it 'the Mother Ditch', as evidenced by numerous articles in early newspapers dating back to 1854. And the zanjero was always referred to as 'the zanjero'. Remember, Spanish was the lingua franca in Los Angeles until well into the 19th-Century. But about that water wheel ... Water pressure is determined by how high above the outlet the water level is initially. That pressure is about 0.45 pounds per square inch, or 0.45 psi. The higher the column of water, the greater the pressure at the outlet. So a plan was executed to raise the pressure by constructing a water wheel on la zanja madre. In May, 1863, a 30- to 40-foot, wooden water wheel, constructed in San Francisco and brought in pieces by boat to Los Angeles, was put into service on the zanja. Various accounts provide differing numbers as to its diameter.) A 40-foot wheel would have raised the water pressure downtown by nearly 18 psi, which was a significant improvement over the original gravity flow from the river. Fortunately, we know exactly what the water wheel looked like, from a photograph taken circa 1870: The trestle-like structure running to the right from the top of the wheel is a wooden flume that moved the water from the wheel to another ditch that was higher on the hill that is in the foreground of the picture. Of interest to Solaneros is the fact that the vantage point of this photograph is almost directly opposite the bottom of Solano Avenue.

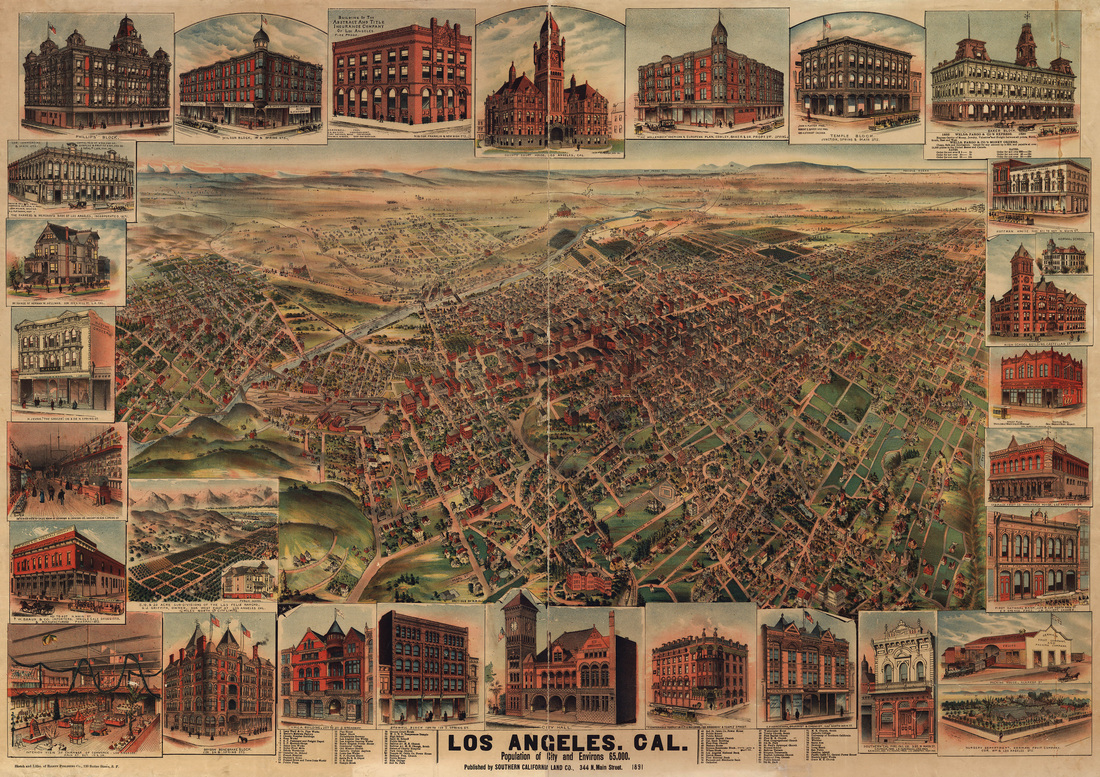

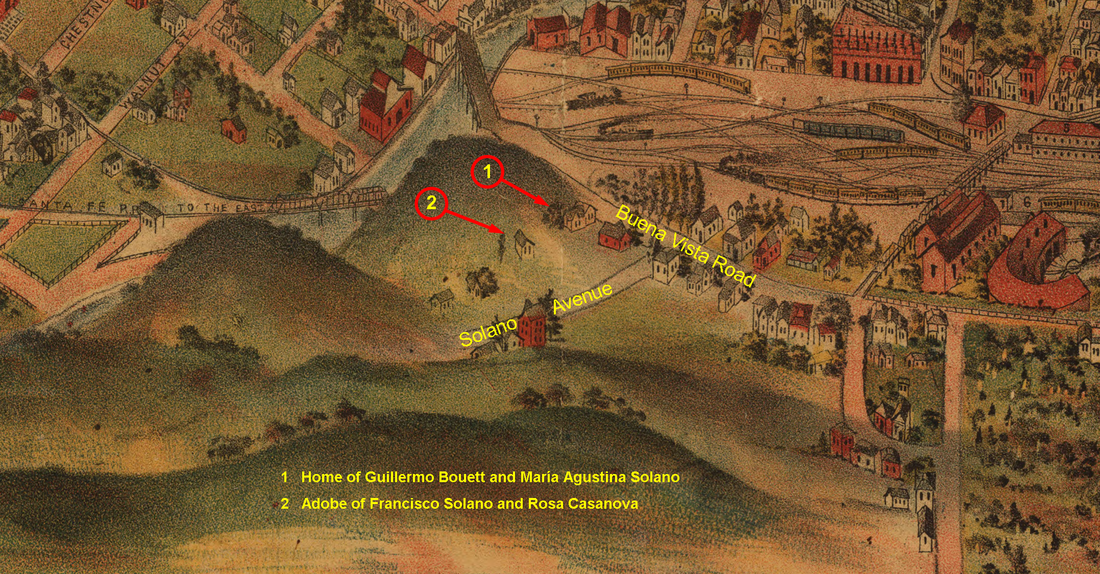

Part 2 of this blog will describe the water wheel in greater detail and pinpoint its location, on both historic maps and a satellite image of the area today. A bird's eye view of Solano Canyon from 1891 The bird's eye view map is a cartographic genre all its own. While they are, indeed, maps, bird's eye views can also be works of art. Their accuracy as maps may be questionable and their value thereby limited, but still ... The second image, below, is but a very small small portion of a large, bird's eye view map of Los Angeles by the San Francisco publisher H. B. Elliott, published in 1891. The original map is huge — 31.9" x 45.3" — and the detail is incredible. This is the original map: Notice that the actual map portion of the whole — the bird's eye view — occupies only about 50% of the total map area. The border is a series of views of 24 buildings, one house, and the interiors of a grocery store and the Chamber of Commerce. But it is that very small area of the map that is of interest here. If we zoom into Solano Canyon, we find some interesting detail. The question, of course, is whether what we are seeing is accurate. The area is readily recognizable: notice the railroad yard with its roundhouse, and Buena Vista Road and Solano Avenue (annotated), the Santa Fe Railroad bridge across the Los Angeles River, and the Buena Vista bridge across the river, as well.

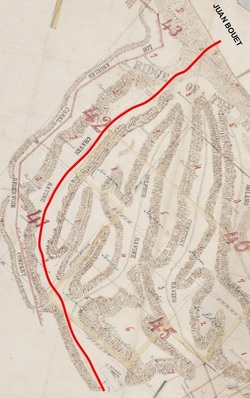

Now look at the annotations numbered 1 and 2. While it is, admittedly, merely speculation and with no assurance of accuracy, it is entirely possible that #1 is the home of María Agustina Solano and her husband, Guillermo Bouett at 1425 Buena Vista Road, and that #2 is the location of the original adobe that was built between 1866 and 1871 by founder Francisco Solano for his wife, Rosa Casanova, and their family. María Agustina Solano, of course, is the daughter of Francisco Solano and Rosa Casanova, and for whom, Bouett Street in Solano Canyon is named. It is known with certainty from other maps, rigorously surveyed and drawn to scale (primarily by Francisco and Rosa's son, Alfredo Solano), that location #2 is the relative location of the adobe, and it is also known with certainty that María Solano and Guillermo Bouett built a house on Lot #100 of the original Solano Tract after 1888 and before 1900, which is located at the corner of (now) North Broadway and Casanova Street. So are we seeing a view from history on this map? One doesn't know for sure, but it surely seems possible. The truth about who owned the land in Chavez RavineFor some reason, there seems always to have existed confusion about who owned the land on which the three so-called Chavez Ravine communities — la Loma, Palo Verde and Bishop — came to be. The answer is simple: With the exception of a small portion of Palo Verde, and all of Bishop, the land originally belonged to Francisco Solano and his heirs. The following map is quite busy, but, hopefully, an explanation will clarify the map. The red rectangle at the lower-right of the map is the original 16-acre Solano Tract that, today, is the lower Solano Canyon community. The large red rectangle is the remaining 70 acres originally purchased by Francisco Solano in 1866 (along with the 16 acre parcel, for a total of 86 acres).

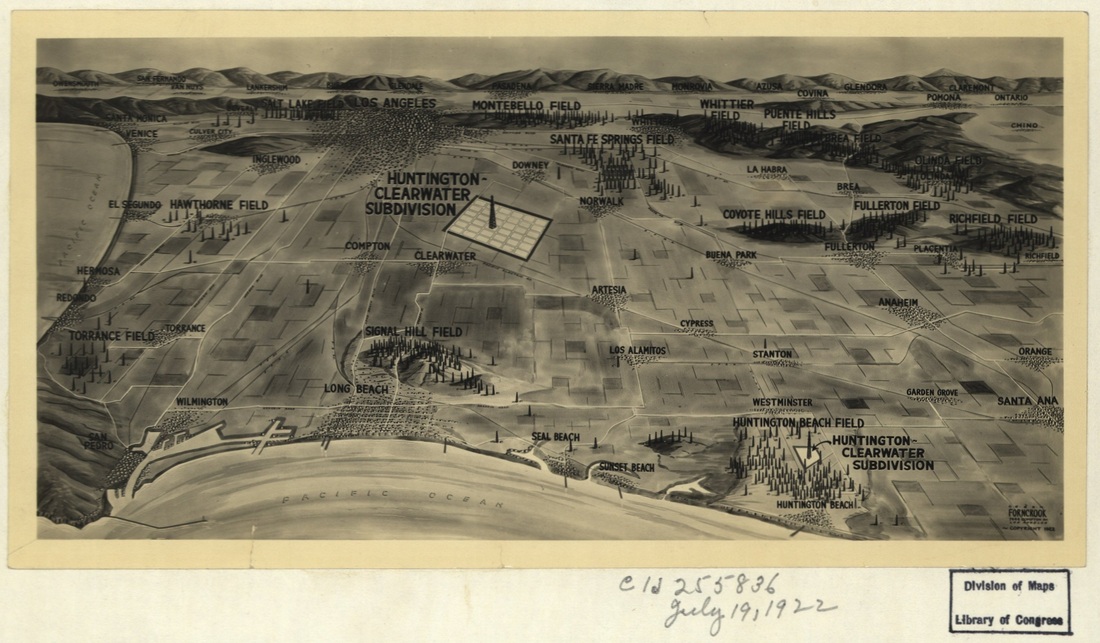

The yellow rectangle is an additional 52½ acres that were purchased by George Hansen and subsequently sold to the heirs of Francisco Solano, making a total of 138½ acres that were owned by Francisco Solano's heirs. The upper portion of Lot 7 (in the red rectangle), plus a small piece of Lot 6 (the upper portion of the yellow rectangle) is Solano Tract No. 2, which is, today, the upper part of Solano Canyon. Where, then were la Loma and Palo Verde? Look at Lots 6 (in yellow) and 7 and 2 (in red): the loma — for which the community of la Loma took its name — can clearly be seen. The blue line in Lot 6 is the remnant of Bishop's Road, and it marked the boundary between la Loma and Palo Verde. The upper blue line is the remnant of Boylston Street. Palo Verde, then, was all of that remaining portion of Lot 6, plus all of Lot 5, between Bishop's Road and Boylston Street. For reference, the blue oval is the LA Police Academy. Bishop was located below Palo Verde, roughly in the upper half of Lot 4 that is labeled "L & J Garibaldi"; in fact, there was a Garibaldi Street in the Bishop community. The double white line between Palo Verde and Bishop was Effie Street. Note that missing altogether is any reference to Julián Cháves. Cháves never owned any of the land that made up any of the so-called Chavez Ravine communities; in fact, the Chavez Ravine communities had nothing at all to do with Chavez Ravine itself; rather, they were located in Sulphur, Cemetery, and Solano Ravines. How the myth of Julián Cháves was inserted into the communities that bore his family name remains a mystery; but, in any case, it is categorically untrue. An interesting article in a recent online issue of LAMag reminds us that there was oilwell drilling activity proposed, and, in fact, executed in the Stone Quarry Hills. Not only that, but exploratory wells were drilled in Solano Canyon itself. I found this article particularly interesting because my academic training is as a petroleum engineer and my professional career was spent as a research scientist and practicing reservoir engineer. The following is an excerpt from an 1895 article in the Los Angeles Herald subtitled Unusual Number of Oil Permits Considered. Clipped from the article is this: The Solano tract referred to here is the 16-acre tract that Francisco Solano bought from the City in 1866; in other words, lower Solano Canyon. Included in the LAMag article is this wonderful map from the Library of Congress that was made by Edna Forncrook of Los Angeles in 1922 that shows graphically the extent of oilwell drilling activity in, and around, Los Angeles, which, by 1922, was extensive. Click to enlarge the map and you will see, between Los Angeles and Glendale-Burbank, and just behind the "L" in "Los Angeles", the Stone Quarry Hills. The original article in LAMag can be found here.

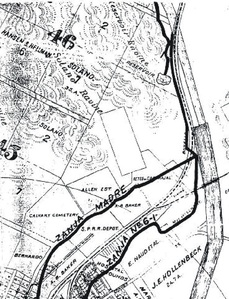

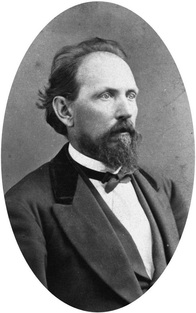

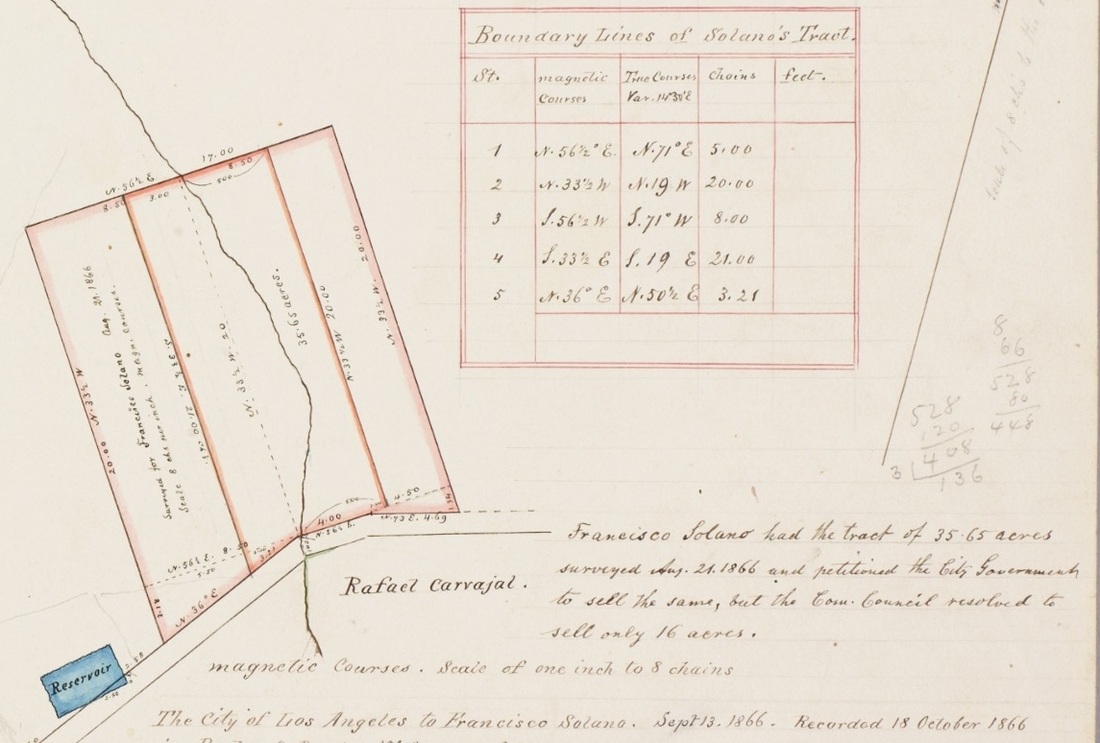

"His was the driving force behind the creation of Solano Canyon"  George Hansen: Austrian immigrant, Gold Rush prospector, early Los Angeles resident, professional surveyor, Los Angeles City and County Surveyor, large land owner, and mentor to Alfred Solano. And, in the process, his was the primary driving force behind the creation of the Solano Canyon. Hansen was a native of Flume on the Dalmation coast of the Austrian Empire. He came to California around Cape Horn in 1850, his goal to prospect for gold in the Mother Lode country; but that having failed, he went to Los Angeles in 1853. He borrowed money, purchased surveying equipment, and began the work of surveying and mapping land around Los Angeles. One of his first projects was to lay out the Anaheim townsite for the Los Angeles Vineyard Society of San Francisco, a group of investors. He took Alfred Solano under his wing, became his mentor and taught him surveying. Eventually, Solano became his ward, and the two men worked together and were in business together (as Hansen & Solano) until Hansen's death in 1897. Unmarried and childless, Hansen left his entire estate to Alfred Solano. Hansen and Solano surveyed the property purchased from the City by Francisco Solano, Alfred's father, in 1888, 17 years after the death of his father and four years after the death of his mother, Rosa Casanova. Alfred Solano subdivided the estate, 87 acres in all, located in the Stone Quarry Hills, for distribution to the heirs of Francisco and Rosa. And the rest, as they say, is history. This is a portion of a map made by George Hansen in 1866. It represents the initial survey of Francisco Solano's purchase from the City of 16.97 acres. Alfred Solano was nine years old at the time; whether he was on the ground with Hansen when this survey was made is not known. The text reads, in part: "Francisco Solano had the tract of 35.65 acres surveyed Aug. 21, 1866 and petitioned the City Government to sell the same, but the City Council resolved to sell only 16 acres ... The City of Los Angeles to Francisco Solano. Sept. 13, 1866. Recorded 18 Oct. 1866"

The term 'Chavez Ravine' means different things to different people. To a historian, it refers to the westernmost ravine on the massíf known, in recent times, as the Stone Quarry Hills, which today includes Elysian Park, the Solano Canyon community, and, of course, Dodger Stadium. To many Angelinos, it means Dodger Stadium on game days: the Boys in Blue, Dodger Dogs, bobbleheads of well-known players, National League Pennants and World Series Titles, and, of course, baseball (but no tailgating). Yet to still others, a dwindling few who call themselves los Desterrados — the exiles — it means having once lived in one of the three communities of la Loma, Palo Verde, or Bishop, known collectively as Chávez Ravine, and it means having been evicted from one's home and, more likely than not, having watched it be destroyed by bulldozers, with armed policemen and newsmen standing idly by, watching and filming the chaos, mostly disinterestedly. Chavez Ravine — the ravine, not any of the rest of it — was a steep canyon that, the geologists will tell you, was one of many ancient channels of the Los Angeles river that was uplifted through tectonic forces millenia ago. By the mid-19th-Century, there was a steep, dusty trail that rose all the way to the summit of the massíf, then passed through a narrow defile and descended to the flat land by the river, an area now known as Frogtown, and where Riverside Drive is today. The land that the trail emptied onto was owned in 1856 by Juan Bouett, the author's 2X-great-grandfather (see the map, above). Mariano and Julián Cháves, brothers from New Mexico Territory, also owned land on the flats adjoining that of Juan Bouett, and on the East side of the river. Julián's land on the west side of the river, 81.75 acres, was deeded to him in 1847 by Esteban Quintero. It is said, and repeated endlessly without proof, that he also owned 83 acres in the ravine near downtown, although I have never seen proof of that claim. I suspect that the 83 acres actually refers to his 81.75 acres by the river. In any case, it is likely that Chavez Ravine takes its name from one, or both, of the Cháves brothers. [Map source: a portion of SR_Map_0377, annotated by the author, The Huntington Library.] |

About the AuthorLawrence Bouett is a retired research scientist and registered professional engineer who now conducts historical and genealogical research full-time. A ninth-generation Californian, his primary historical research interests are Los Angeles in general and the Stone Quarry Hills in particular. His ancestors arrived in California with Portolá in 1769 and came to Los Angeles from Mission San Gabriel with the pobladores on September 4, 1781. Lawrence Bouett may be contacted directly here.

Archives

July 2018

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed