|

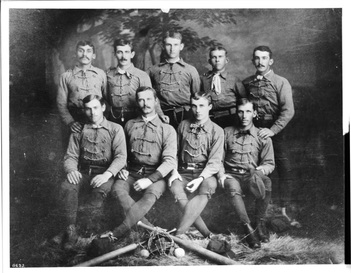

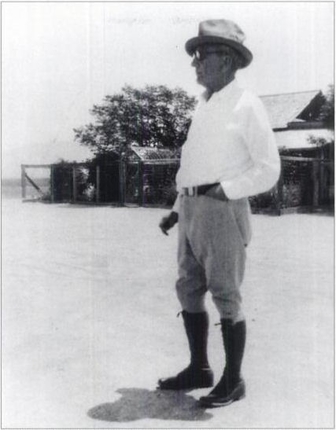

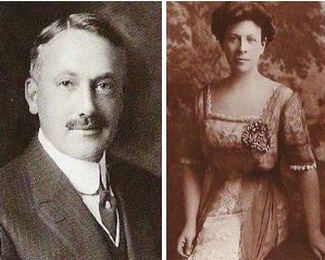

Alfredo Solano, or Alfred as he was known for most of his adult life, was born in Los Angeles 02 May 1857, the second child and first son of Francisco Sales de Jesús Solano and María Rosa de las Mercedes Casanova, immigrants from Costa Rica about 1850. He died, also in Los Angeles, 14 November 1943 at age 86. He was married three times, to Ella T. Brooks, Minnie Belle Classey, and Kathryn E. Hathaway, and he produced no children. He is buried at Forest Lawn cemetery in Glendale, California. This is the first of a series of blogs that will feature the lives of "People of Solano Canyon" — individuals who are important to the development of the Solano Canyon community — from its founding in 1866 to the present day. More may be read about these Solano Canyon champions on their individual pages under History, People of Solano on this website.  George Hansen, ca. 1857 [Anaheim Public Library P457] George Hansen, ca. 1857 [Anaheim Public Library P457] A wag once said that the point to life is to make the distance between the dates on one's tombstone as great as possible; but it seems to me that it is the quality of what lies between those dates that is what really matters. By the latter definition, the life of Alfred Solano was a full one, and one that truly mattered. Alfred's parents immigrated to Los Angeles from Costa Rica sometime between November 1847, when Rosa Casanova's youngest sister, María Teodora, was baptized in Costa Rica, and April 1850, when her father, Antonio Casanova, died in Los Angeles of bronchitis. [Click here for an example of how a family story that has been passed down from generation-to-generation can be completely misleading even though it contains a grain of truth.] Alfred is found in the 1870 census, at the age of 14, living in the household of George Hansen and Hansen's long-time, live-in housekeeper, Francisca García. In 1880, the two men were lodgers in the home of J. S. Crawford, a Los Angeles dentist and a widower. Exactly when, and how, Alfred made Hansen's acquaintance is not known; but Hansen was a surveyor and civil engineer, and it is likely that Alfred took an interest in the work. Hansen became Alfred's mentor, and the two of them went into the surveying business together as Hansen & Solano, an arrangement that was maintained until Hansen's death in 1897. When he died, George Hansen left his entire estate to Alfred. Alfred is referred to in several places and at different times as Hansen's ward, although whether that is true in a legal sense is not known. In 1875, George Hansen and his protégé, Alfred, left Los Angeles by steamer and traveled to San Francisco. The following day, they took the ferry across San Francisco Bay to Berkeley, where Alfred was introduced to the Chancellor of the University of California. As a result of that meeting, Alfred was enrolled in the Engineering College. He began his civil engineering studies in Berkeley at the start of the next term, but he probably only attended for one or two semesters before returning to Los Angeles, apparently homesick. There is no record of his course of study, nor of whether he graduated. Whether Alfred ever lived with his parents and siblings in the adobe that his father build on the stream in what became known as Solano Cañon — later Solano Ravine — is not known, but after his father died in 1871, it is known from his diaries that Alfred helped care for the needs of his mother, Rosa Casanova, and his five siblings: Josefina, Alejandro, María, Manuel, and Alonzo. In one entry, he documents his having purchased two bibles, one for each of his two sisters. One of the bibles was destroyed in a house fire about 25 years ago; the other one is still with a descendant, and which the author has seen. It contains some valuable genealogical information. Alfred took pains to preserve the 87 acres of land that his father had purchased from the City of Los Angeles in 1866. He refers in his diaries to his awareness of the value of his family's retaining the land as a legacy. At the same time, he threw himself into his surveying work with George Hansen as well as the social scene in Los Angeles. He was one of the founding members of the Los Angeles Athletic Club (LAAC) and, in what may be the only extant photograph of him as a young man, Alfred was a member of the LAAC baseball team in 1884. Alfred is the person in the back row, at the far left. After Alfred married the widow, Ella T. Brooks, in 1886, the couple quickly rose to prominence in Los Angeles social circles. They built a large mansion on Figueroa Street at 23rd Street in 1896 and, in 1904, they purchased the 30-room Stimson House, which still stands at 2421 South Figueroa Street. They entertained lavishly and Alfred acquired considerable political influence, although he never ran for political office himself. It was partly that political influence and the respect with which he was held by the City Council that allowed him to be a responsible conservator or his parents' land in the Stone Quarry Hills. He was, at various times, Assistant City Surveyor and City Surveyor of Los Angeles, and County Surveyor of Los Angeles County. Although Alfred never lived in Solano Canyon — at least, not as an adult — he is nevertheless the single person who is most responsible for the existence of the Solano Canyon community today. This is one of only a small handful of snapshots of Alfred Solano as an adult. This photograph was taken in the Palo Verde Valley in Blythe, California about 1930. Alfred Solano did many other interesting things in his life. He taught mining engineering at USC in 1918 (the author has one of his examinations), prospected for minerals in California and Arizona and gems in South America (the author has an emerald ring made from one of the stones Alfred brought back), and he told the author's father that he was with Jimmy Angel when Angel accidentally discovered Angel Falls, the world's highest waterfall, in Venezuela in 1933; Alfred was 75 years old at the time. Angel Falls has a 3,212-foot total drop, with a free drop of 2,648 feet. It is worth watching this video of Angel Falls, and reading this article. This fall is named for Jimmy Angel, an adventurous pilot from Missouri, United States, who flew to the air circus Lindberg. James Crawford Angel (Jimmy Angel) is a modern legend. He saw the waterfall for the first time in 1933 with his partner while searching for the legendary McCracken River of Gold, or the Golden City. Jimmy Angel's partner mentioned in the article is Alfred Solano, patron of Solano Canyon.

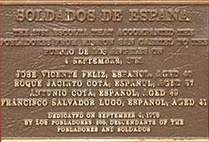

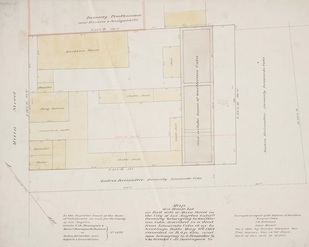

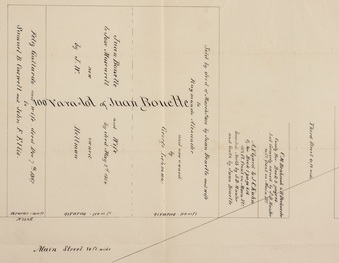

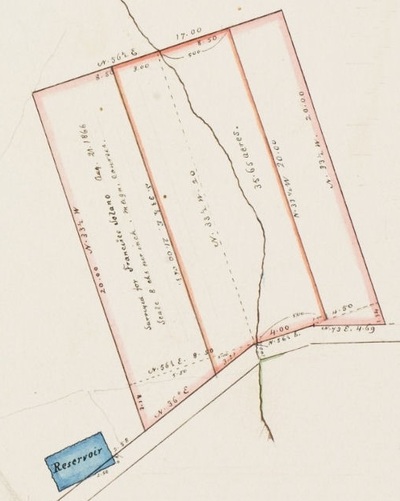

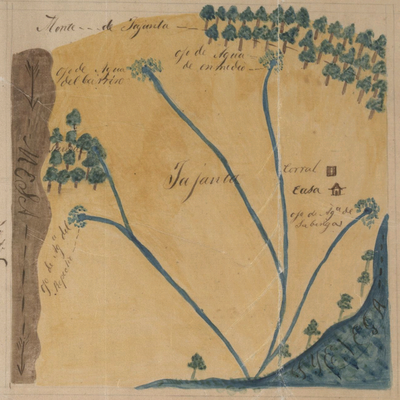

A personal family journey This blog is about my own family history and why Solano Canyon means so much to me, 246 years after the first of my ancestors came to California in 1769. It is an attempt to explain why the 3/16 part of my blood that is Hispanic has become the most important part of my ethnic heritage and the part of which I am the most proud. I hope you will share this journey with me. José Manuel Pérez Nieto Manuel Nieto was born circa 1734 in la Villa de San Felipe y Santiago de Sinaloa, Nueva España, more commonly called simply la Villa de Sinaloa. His mother is Manuela Pérez and his father is José Nieto. In the 1790 padrón (census) of the Presidio of San Diego, Manuel Nieto, mulato, is listed along with his mother, Manuela Pérez, española, which means, in the rigid racial classification system in place at the time, that Manuel's father, who is not listed and is presumably dead by then, was black. Manuel Nieto is the first of my ancestors to have come into what is now the State of California, as a soldier in the company of Gaspar Portolá. Manuel Nieto married María Teresa Morillo, a native of Loreto in what is now Baja California, about 1775, presumably in Loreto. They had six children, one of whom is a daughter, María Manuela Antonia Pérez Nieto. María Manuela Antonia Pérez Nieto Manuela Nieto was the fifth of six children of Manuel Nieto and María Teresa Morrillo. She was baptized at Mission San Gabriel in 1791. When her father died in 1804, she inherited Rancho los Cerritos, one of the five ranchitos that once made up the vast Rancho la Zanja, the 330,000-acre grant of her father's from King Carlos III of Spain in 1784, the second of only four such royal grants in California. The boundaries of the grand were defined as "... all the land between the San Gabriel and Santa Ana Rivers, and from the crest of the Saddleback Mountains to the sea." Roque Jacinto de Cota Roque Cota was born circa 1724 in the mysterious Villa del Fuerte in what is now Sinaloa, México. He married Juana María Rita Verdugo in Loreto (now in Baja California) circa 1755. They had 11 children, of whom, the fourth was Juan Ygnacio Guillermo, who was born in Loreto circa 1768, and of whom, more later. Roque Cota was a soldado de cuera, a so-called 'leather-jacket' soldier in the Spanish Colonial army. He was one of four soldiers who comprised the escolta (escort) who came to Los Angeles from Mission San Gabriel along with the 44 pobladores (settlers, literally 'residents') who first settled what is now Los Angeles, arriving September 4, 1781. His name is memorialized on a bronze plaque in the Plaza of downtown Los Angeles, along with that of his younger brother, Antonio, who was also a member of the escolta. Juan Ygnacio Guillermo Cota Guillermo Cota was born circa 1768 in Loreto, the fourth of 11 children of Roque Cota and Juana María Verdugo. He married first, María Manuela de Jesús Lisalde in 1794 at Mission San Gabriel Arcángel. They had four children before Manuela died at Santa Bárbara in 1803. Hers is one of the earliest burials in the Mission at Santa Bárbara. Guillermo married, second, at Mission San Gabriel in 1805, 13-year-old Manuela Nieto, daughter of Manuel Nieto. They had 13 children, of whom, the ninth was María Loreta Cota, born in 1824 and baptized in the downtown Plaza Church. Guillermo Cota was alcalde mayor (mayor) of the Pueblo of Los Angeles three times: 1798–1799, again in 1824, and finally in 1827–1828. He once had a large lot and an adobe house on Main Street. María Loreta Cota Loreta Cota was born in Los Angeles and baptized in the Plaza Church in 1824, the daughter of Guillermo Cota and Manuela Nieto. In May, 1847, when she was 22 years old, the ayntamiento (city government) granted her title to a 100-vara (278.1 feet) square lot downtown. The property was located in what is now about 2/3 of the block between Main and Spring Streets and between Third and Fourth Streets, beginning about 90 feet south of Third Street. She died a widow in Los Angeles in 1905. Jean Bouet Meanwhile in France, Jean Bouet was born in 1813 in Mont-de-Marsan, a village about 50 miles south of Bordeaux, the sixth of six children of Antoine Agustín Bouët and Jeanne Dauga. When he arrived in California is not certain, but it was around 1830. In any case, he became known as Juan Bouet, and he married Loreta Cota in the Plaza Church in 1847. They had eight children, the sixth of whom was a son, Guillermo, of whom, more later. Juan Bouet owned land just northeast of the Stone Quarry Hills as shown on an 1868 map, in an area by the Los Angeles River that is today called Frogtown. His neighbors, as may be seen, were Mariano and Julián Chávez.  Guillermo Bouett, ca. 1890 Guillermo Bouett, ca. 1890 Guillermo Bouett Guillermo Bouett was born in Los Angeles in October 1857, the sixth child of Juan Bouett and Loreta Cota. He eventually became a Captain in the Los Angeles County Sheriff's Department and was killed in the line of duty in 1913. The story of his death, while tragic, is not without its element of humor, at least when seen from the distance more than of 100 years. William Bouett, as he was called, had a favorite horse named Jack. Jack was trained so that he could be mounted from the rear. William Bouett simply ran up to his horse, put his hands on Jack's haunches, and leapt aboard. Captain Bouett was working with a chain gang in 1913 near Azusa, when one of the prisoners, who had been unshackled so he could get a drink of warer, saw an opportunity to escape and he began to run. The Captain, seeing the fleeing prisoner, ran to Jack and leapt on. He got one boot in a stirrup, but Jack took off a moment too soon. Captain Bouett was thrown, and when he fell, he broke his neck and was killed instantly. His body was brought back to Los Angeles in a wagon. Francisco Sales de Jesús Solano .Francisco Solano was born in 1817 in Ujarrás, in the province of Cartago in Costa Rica. He is the son of Felipe Solano and Juana Alvarado. The Solano line is an old one in Costa Rica, probably going back to a Spaniard of the same surname who arrived on the Caribbean coast in 1565 as a soldier.  María Agustina Solano, ca. 1880 María Agustina Solano, ca. 1880 María Rosa de las Mercedes Casanova Rosa Casanova was born on the Mosquito Coast of Costa Rica or Honduras in 1840, the second of four daughters of Antonio Casanova of Sant Felíe de Guixols in Cataluña, Spain and María Trinidad Serrano Puentes of Maracaibo in Zulia, Venezuela. Antonio and Trinidad had one daughter in Jamaica, then Rosa, then two others in Costa Rica. One of the daughters did not survive to adulthood. Rosa's father, Antonio Casanova, and Francisco Solano somehow became acquainted, and when the Casanova family left Costa Rica for Los Angeles sometime between 1848 and 1850, Francisco Solano accompanied them. Thirty-seven-year-old Francisco Solano and 13-year-old Rosa Casanova were married by a juez de paz (Justice of the Peace) in Los Angeles in 1854; they were re-married in the Plaza Church by a priest in 1857. They had six children, the second of whom was Alfredo, born in 1857, and the fourth of whom was María Agustina, born in 1862. María Agustina Solano María Solano was born in Los Angeles in 1861. Shortly after 1866, when her father, Francisco Solano, bought 87 acres of land in the Stone Quarry Hills, she moved into what is now Solano Ravine to an adobe that was built for his family by her father. It must have been a very quiet life up in the hills, living on a stream what flowed from a spring higher up the ravine. María Agustina Solano and Guillermo Bouett were married in the Plaza Church in Los Angeles in 1881. They built a house during the 1890s at 1425 Buena Vista Road, on the corner of Buena Vista Road and Casanova Street, where they lived until William Bouett's death in 1913; María continued to live in the house until shortly before 1920, when she moved to Long Beach to live with one of her daughters. The retaining wall for the lot is constructed from mortared stone that was quarried from the Stone Quarry Hills and is still visible on North Broadway at Casanova Street. Why I Love Solano Canyon This rather long narrative has finally come to an end. It has brought together at least four strands of my ancestry — one French and three Hispanic — that have brought me, over nine generations and 325 years from 1680 in San José del Cabo in Baja California to the present, to Solano Canyon in Los Angeles, California. I feel as if Solano Canyon is my home, despite the fact that I have never lived there. When I walk its streets, I can feel my ancestors — Nieto and Morillo, Cota and Verdugo, Solano and Casanova, and Bouett and Solano — especially my great-grandparents, Guillermo Bouett and María Solano, but also María's brother Alfredo Solano, all of whom contributed in some way to make me who I am, and all of whom contributed to the fact that Solano Canyon is a community today. It is these people on whose shoulders I stand, and Solano Canyon is the physical manifestation of that pedestal. When I am in Solano Canyon, I feel like I am at home. And that is why I love Solano Canyon. Puede que Díos bendice a la gente de Solano Cañon — mis hermanos, mis primos, mis amigos. For those who want a quick tour of Solano Canyon, which will celebrate its 150th anniversary in 2016. Historic Solano Canyon is on the cusp of its sesquicentennial, the 150th anniversary of the founding of the community. This brief tour explains how Solano Canyon came to be what it is today: quite possibly, in the eyes of its residents, the best place to live in all of Los Angeles. Francisco Sales de Jesús Solano, a Costa Rican immigrant to Los Angeles in 1850, and who maintained a meat-packing business in Sonoratown, just north of the placita, had a 35-acre tract of land in an unnamed ravine in the Stone Quarry Hills surveyed on August 21, 1866. The 35-acre tract is the larger block that is outlined in red on the following map. He then petitioned the City government for title to the land. The City agreed to sell the land, but only 17 acres, which was deeded to him on September 13th and recorded on October 18th that same year, and for which, he paid the City $6. The 17-acre tract that Francisco received is the narrower block, also outlined in red, in the center of the map. Notice the stream in the center of the tract that flowed from a spring higher up in the ravine.  Portion of SR Map 377, The Huntington Library Portion of SR Map 377, The Huntington Library Solano immediately began to build an adobe on the stream on his newly-acquired property, and he moved his family up to the ravine, which soon became known as Solano Cañon. We know the exact location of the adobe from the map at left. The adobe is the small square on the stream immediately above the final letter "O" in "SOLANO". The dashed line to the left of the stream is a trail that went up the ravine. But Francisco Solano died suddenly on December 7, 1871 at the age of 54. He was buried in the Catholic Cemetery on Calle Eternidad, which was later called Eternity Street, then Buena Vista Road, and finally present-day North Broadway. His wife, Rosa Casanova, continued to live with her six children in Solano Cañon for several years, but she eventually took her children and moved from the ravine to the home of her mother, María Trinidad Serrano Puentes, who lived on Bath Street in downtown Los Angeles, near the plaza. Rosa remarried in 1877, and she died in 1884 at the age of 43 at another of the family's properties, Rancho Tajáuta, a portion of which was the family farm and which was located about 12 miles south of the city. Rancho la Tajáuta, which was a Gabrielino/Tongva place name, was originally a 3,560-acre Mexican land grant from 1843, and today it is the Los Angeles neighborhoods of Willowbrook and Watts. The diseño, below, is by Henry Hancock, et al, and probably dates from about 1858 or earlier. Notice the detail on the map, including the locations of a corral and a casa, a sausal (willow grove), and the four ojos de agua (springs), all of which are named. In 1888, Alfred Solano, son of Francisco Solano and Rosa Casanova, surveyed the 17-acre Solano Tract and subdivided it into 100 house lots, which were then distributed to the heirs of Francisco and Rosa. [See the blog, A Date to Remember: April 24, 1888, for more detail.] Soon, houses began to be built in Solano Canyon, and the future of the community was thereby assured. The upper part of present-day Solano Canyon, called Solano Tract No. 2, was added in 1903, and by 1940, the Solano Canyon community had more than 300 households. It is important to note that Solano Canyon, although it is a part of the area that was later called Chavez Ravine, and which included the communities of la Loma, Palo Verde, and Bishop, survived the evictions of the 1950s. An historical note: the author's father and paternal grandfather both were raised in Solano Canyon, and both attended the original Solano Avenue elementary school.

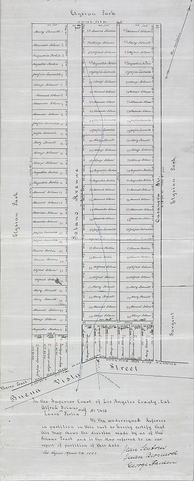

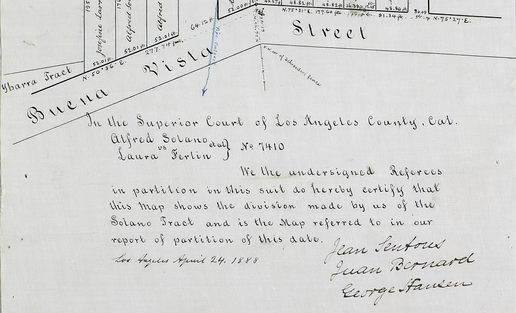

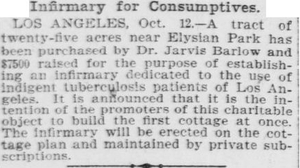

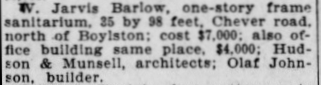

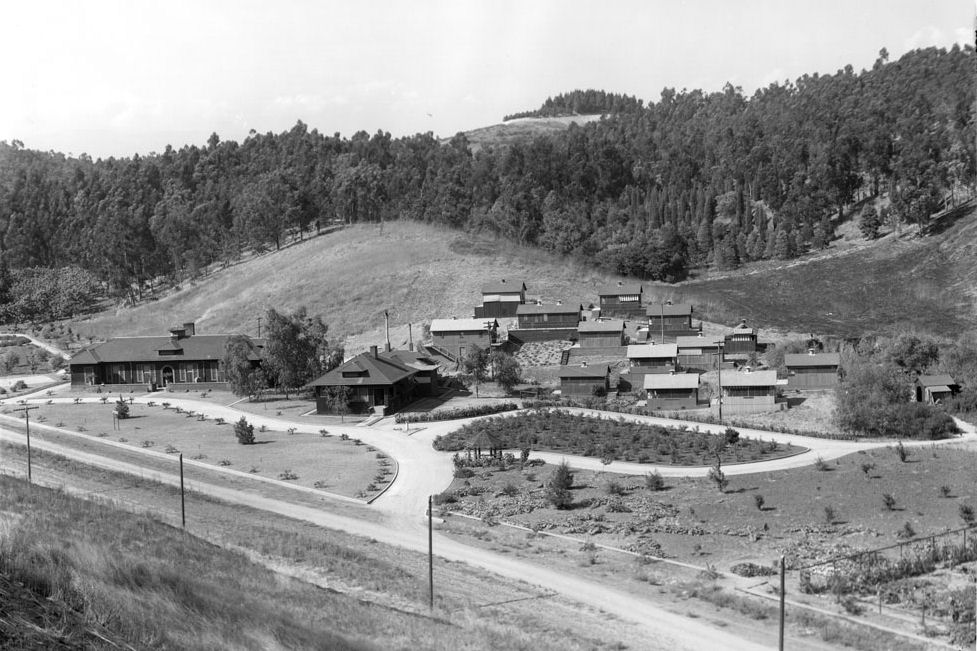

Note: 'A dste to remember' is a blog series that speaks to the importance Solano Canyon begins to grow as a community April 24 is an important date in Solano Canyon history because on that date in 1888, in the Superior Court of Los Angeles, the referees in case No. 7410, Alfred Solano et al. vs. Laura Ferlin, signed the survey of the 17-acre tract that became what is, today, the lower part of the Solano Canyon community.  SR Map 32(23), The Huntington Library SR Map 32(23), The Huntington Library Laura Ferlin is Alfred Solano's half sister; his mother, Rosa Casanova, married Laura's father, Agustín Ferlin, following the death of her first husband, Francisco Solano. Laura eventually became Alfred's ward, and she changed her surname to Solano. Alfred and the other heirs were not suing Laura Ferlin for any adversarial purpose; rather, the lawsuit was the best way to have the Court define the disposition of Francisco Solano's estate which consisted primarily of 87 acres of land.. The lawsuit determined that there were 84 shares in the estate. All six of Francisco's children — Josefina, Alfredo, Alejandro, María Agustina, Manuel, and Alonzo Francisco — plus Laura Ferlin and her father, Agustín Ferlin, were legatees. With the division of the estate thus determined, Alfred, the eldest son but also a professional surveyor, divided the 17 acre tract into 100 lots which were then assigned to the heirs as shown in the complete map, which is reproduced in full at left. [Click on the map to see a larger version.] With ownership settled and title in hand, Alfred, on behalf of the heirs of Francisco Solano, was now free to distribute the 100 lots among the heirs, who were then themselves free to dispose of their lots as they chose. Some sold immediately, while others retained their lots. Alfred bought many of the lots from his siblings. Alfredo Solano, the careful conservator of his father's legacy, thereby assured that Solano Canyon would endure to the present day as a viable community. Historic Solano Canyon will celebrate its sesquicentennial anniversary — 150 years — in 2016. [The referees were an interesting group; for an explanation of who they are, click here.] Part 1: The Beginnings of the Barlow Sanatorium The Barlow Sanatorium, now the Barlow Respiratory Hospital that is affiliated with the USC Medical School, has an intimate connection with the history of Solano Canyon. This is what the main building at the Barlow Respiratory Hospital looks like today: But this is today; so some history is in order. Sometime between 1875 and 1880, a young widow, Ella Brooks, and her two daughters, Marian and Jessie, then younger than 8 and 5 years old, respectively, moved to Los Angeles. Ella, no older than 28 herself, along with her two sisters, Jessie and Hattie, were the daughters and heirs to the fortune of Horatio and Julia Brooks. Horatio Brooks founded the Brooks Locomotive Works of Dunkirk, New York, manufacturers of steam locomotives from 1869 until its merger with several other companies to form the American Locomotive Company in 1901. Horatio Brooks, Ella's father, died in 1887; her mother, Julia, died in 1896. Not long after her arrival in Los Angeles, Ella Brooks met Alfredo Solano, son of the founders of Solano Canyon, Francisco Solano and Rosa Casanova. Alfred and Ella married in New York on November 4, 1886 and returned to Los Angeles shortly thereafter. Meanwhile, in 1895, a young, Princeton-educated physician (M.D., 1892) learned that he had contracted tuberculosis, Which was then known as consumption or the white plague. Determined to cure himself of this often-fatal disease, he came to Los Angeles in search of a warmer, drier climate than that of his native New York. In 1897, Alfred and Ella Brooks Solano built a house at 2302 South Figueroa Street in Los Angeles. The Los Angeles Herald described the mansion thusly: During the year some very beautiful homes have been erected in various parts of the city ... The home of Alfred Solano, at the southeast corner of Figueroa and Twenty-third streets, is undoubtedly one of the most beautiful, not only of the year, but in the city. [Los Angeles Herald, 26 December 1897] The Herald goes on to describe the elegant home in great detail. Meanwhile, 30-year-old Dr. Walter Jarvis Barlow, having recovered from his bout with tuberculosis and established himself in a growing medical practice in Los Angeles, met 26-year-old Marian Brooks Patterson, Ella's daughter, and the two were married in 1898. Eventually, the newlywed Barlows bought a house at 2329 South Figueroa Street, thereby living close to Alfred and Ella Brooks Solano. The Barlows were Ella Brooks Solano's daughter and son-in-law, and, by virtue of his marriage to Ella, they were the same to Alfred. Dr. Jarvis Barlow (he was always called 'Jarvis') began treating tubercular patients in Los Angeles as early as 1898. He had dreamed, since his own recovery from tuberculosis, of opening a free respiratory clinic to treat such patients, especially those who were poor and indigent, because, although tuberculosis, being an airborne disease, can strike anyone, it took a particular toll on those who lived in less sanitary conditions and could not afford to pay for professional care. Dr. Barlow located a 25-acre plot of land on Chavez Ravine Road that was owned by businessman and large landowner J. B. Lankershim. The land was away from the city and possessed, in addition to rural views, a continuous movement of fresh air that would be beneficial to patients with tuberculosis. Alfred Solano took up Dr. Barlow's cause. He knew Lankershim from earlier business dealings and arranged to purchase the land for $7,300. Dr. Barlow paid $5,000, Alfred and Ella contributed $1,300, and Lankershim himself put up the remaining $1,000. Architects Hudson & Mansell donated their services for drawing up the plans, and building permits were issued on April 13, 1902 for the hospital and administration buildings. Incredibly, the infirmary opened in 1902. This is a view of the complex circa 1915; the view is looking across Chavez Ravine Road. The layout is a so-called cottage plan, with the main hospital (left) and administration (second from left) buildings adjacent to patient cottages. In the early years, funds to construct the cottages were donated by prominent residents of Los Angeles. The first cottage was built with money donated by Alfred and Ella Brooks Solano, and it was known as Solano Cottage.

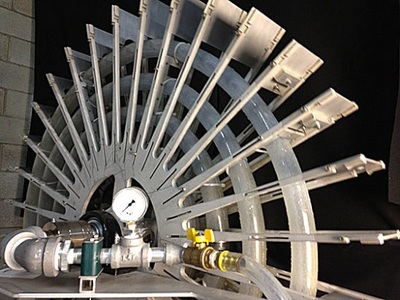

In keeping with Dr. Barlow's desire to care for those who could not afford to pay for their care, patients were charged no fees. Next: Part 2: 113 Years of the Barlow Sanatorium The water wheel on la Zanja Madre: Part 3 In Part 1 of this three-part blog, Where was the water wheel?, we discussed the fact of the water wheel and its importance in helping to provide water to downtown Los Angeles and the surrounding agricultural area. Part 2 provided proof of the physical location of the water wheel and its original location relative to today's map. Part 3 is the final blog in this series. We discuss the rediscovery — one of many — of la zanja madre and how Metabolic Studio's project, Bending the River Back Into the City project re-creates the original wooden water wheel with a modern, fully-functional water wheel, called LA Noria, one of whose goals will be to provide water to assist in irrigation of the Los Angeles Historic State Park. The original zanja system was a network of dirt ditches, which were replaced, over time, with wooden flumes, wooden pipes, and brick pipes. The dirt ditches, of course, no longer exist. The wooden and brick pipes have been discovered and rediscovered several times in recent history. A major, and most recent, rediscovery was made in 2014 during excavation for construction of Blossom Plaza in Chinatown. A section of the brick zanja, which is about four feet in diameter, will be preserved. The new water wheel, LA Noria, brings the story of la zanja madre and its 1863 water wheel full-circle, and is a welcome addition to the never-ending and fascinating story of the history of Los Angeles.

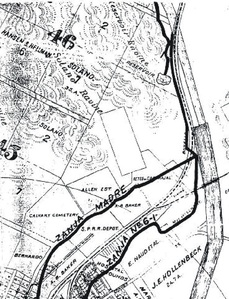

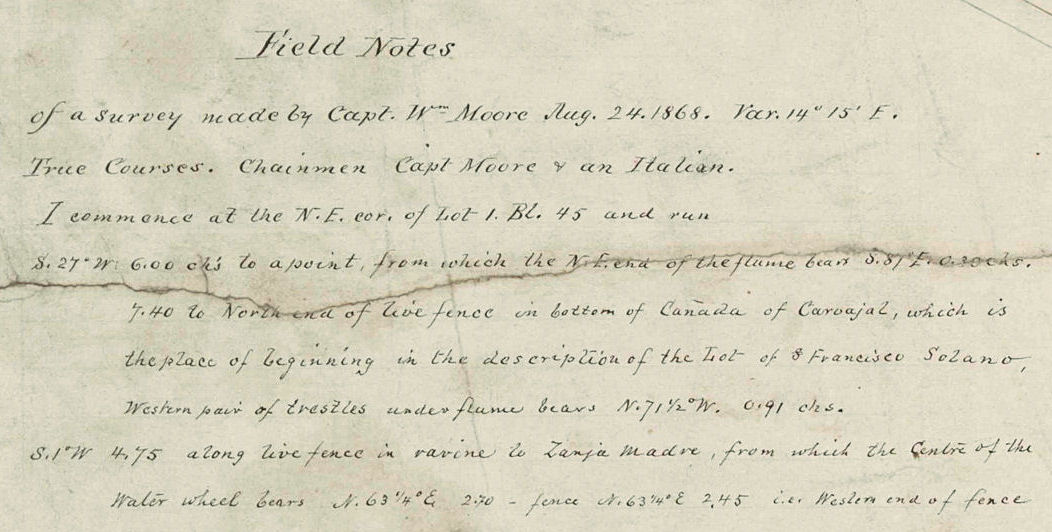

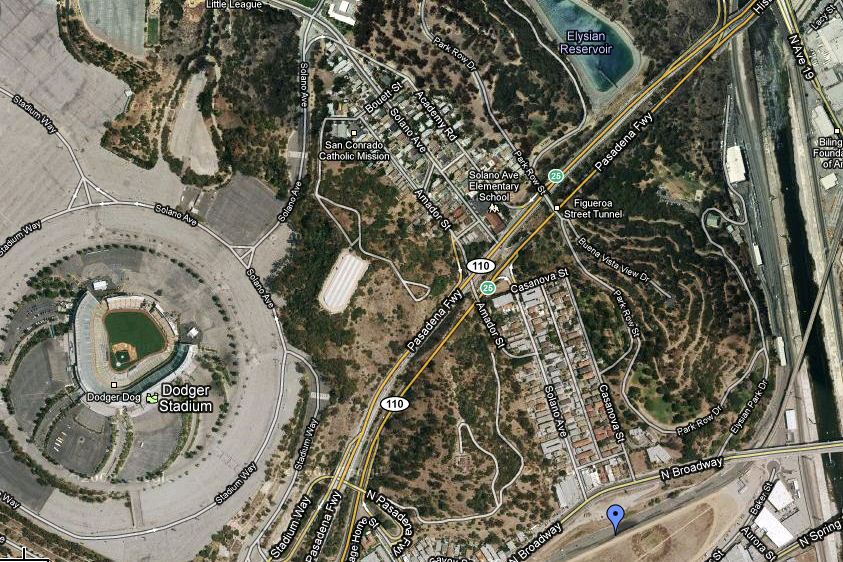

The water wheel on la Zanja Madre: Part 2 In Part 1 of Where was the water wheel?, we said that the water wheel was located near the bottom of Solano Avenue. How do we know that? In 1868, Capt. William Moore, a Los Angeles surveyor, ran a survey to the center of the water wheel. His field notes, copied onto his map of the survey, are explicit enough that we could follow them today. This is a portion of the map that Capt. Moore produced from that survey, which showed City donation lots, the Catholic cemetery, and la zanja madre. In addition, he surveyed the location of the center of the water wheel. Francisco Solano's 87 acres are also shown on the map. Moore wrote extensive field notes directly on the map; his notes for locating the water wheel are shown below. Moore's field notes will not have any real meaning to anyone who is not familiar with surveying; they are presented here as evidence for the claim that the exact location of the water wheel is known with certainty. The location of the water wheel is pinpointed on this satellite image of the area today: Running nearly vertically through the center of the image is the Solano Canyon community, bisected by the Pasadena Freeway, CA-110. To the left is Solano Canyon's hulking neighbor, Dodger Stadium. And to the bottom right, at the blue pin, is the location of the water wheel, just over the embankment at the bottom of Solano Avenue on the edge of the Los Angeles Historic State Park.

Part 3 of this blog will explore the recent rediscovery of la zanja madre and how a new, modern, fully-functioning water wheel, designed by Metabolic Studio's Lauren Bon, will be incorporated into the plan for the Los Angeles Historic State Park. The water wheel on la Zanja Madre: Part 1  from Olmstead, 1910, after Stevenson, 1876 from Olmstead, 1910, after Stevenson, 1876 Not everyone is aware that there was a water wheel on la Zanja Madre. La Zanja Madre was the ditch that brought water from the Los Angeles River to downtown Los Angeles for more than 125 years. The first zanja was dug almost immetiately after the founding of the pueblo in 1781 because Los Angeles was initially a farming community; agriculture requires a significant amount of water and Los Angeles has a very dry climate.. Eventually, responsibility for the zanja fell to a person known as the zanjero, who was charged with keeping the zanja clear of grasses, obstructions, and dead animals (a lovely image, right? But it's true ...). The zanjero was a public official, responsible for issuing permits to use water from the zanja and collecting use fees from water users. He was paid a salary out of municipal funds. There seems to be a compulsion today on the part of some to refer to la zanja madre as 'the Mother Ditch', but that latter term is simply a literal translation of la zanja madre from the Spanish. Rest assured that no one in early Los Angeles ever called it 'the Mother Ditch', as evidenced by numerous articles in early newspapers dating back to 1854. And the zanjero was always referred to as 'the zanjero'. Remember, Spanish was the lingua franca in Los Angeles until well into the 19th-Century. But about that water wheel ... Water pressure is determined by how high above the outlet the water level is initially. That pressure is about 0.45 pounds per square inch, or 0.45 psi. The higher the column of water, the greater the pressure at the outlet. So a plan was executed to raise the pressure by constructing a water wheel on la zanja madre. In May, 1863, a 30- to 40-foot, wooden water wheel, constructed in San Francisco and brought in pieces by boat to Los Angeles, was put into service on the zanja. Various accounts provide differing numbers as to its diameter.) A 40-foot wheel would have raised the water pressure downtown by nearly 18 psi, which was a significant improvement over the original gravity flow from the river. Fortunately, we know exactly what the water wheel looked like, from a photograph taken circa 1870: The trestle-like structure running to the right from the top of the wheel is a wooden flume that moved the water from the wheel to another ditch that was higher on the hill that is in the foreground of the picture. Of interest to Solaneros is the fact that the vantage point of this photograph is almost directly opposite the bottom of Solano Avenue.

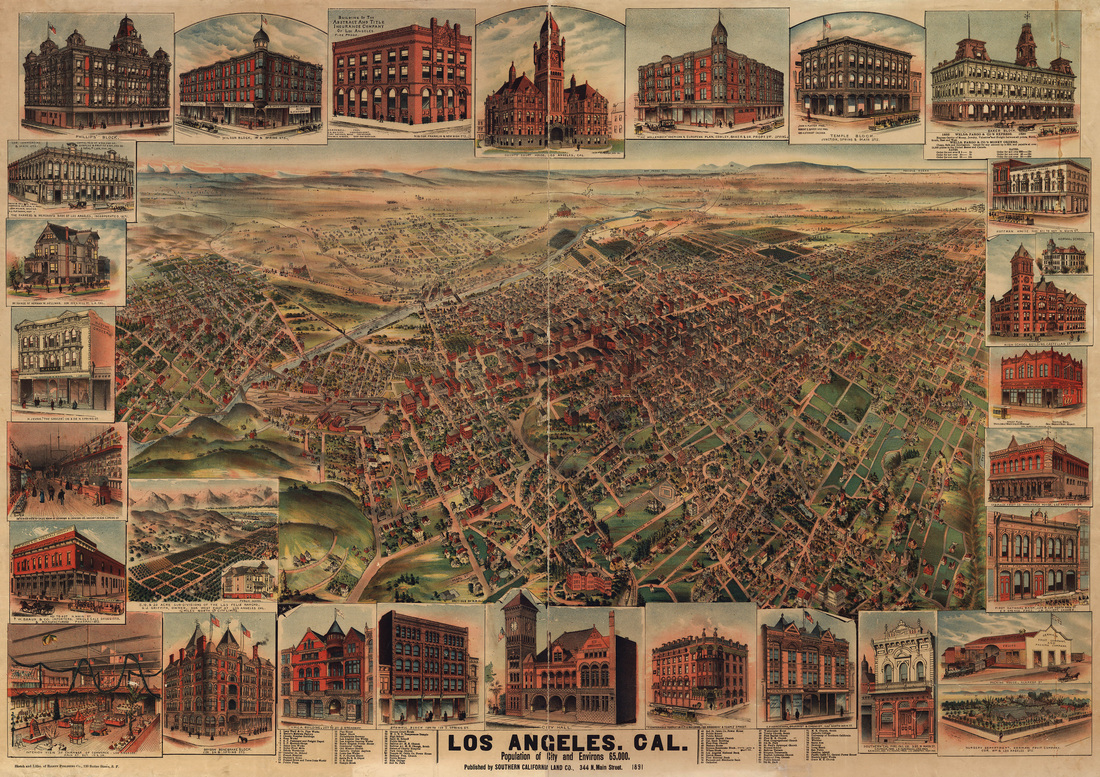

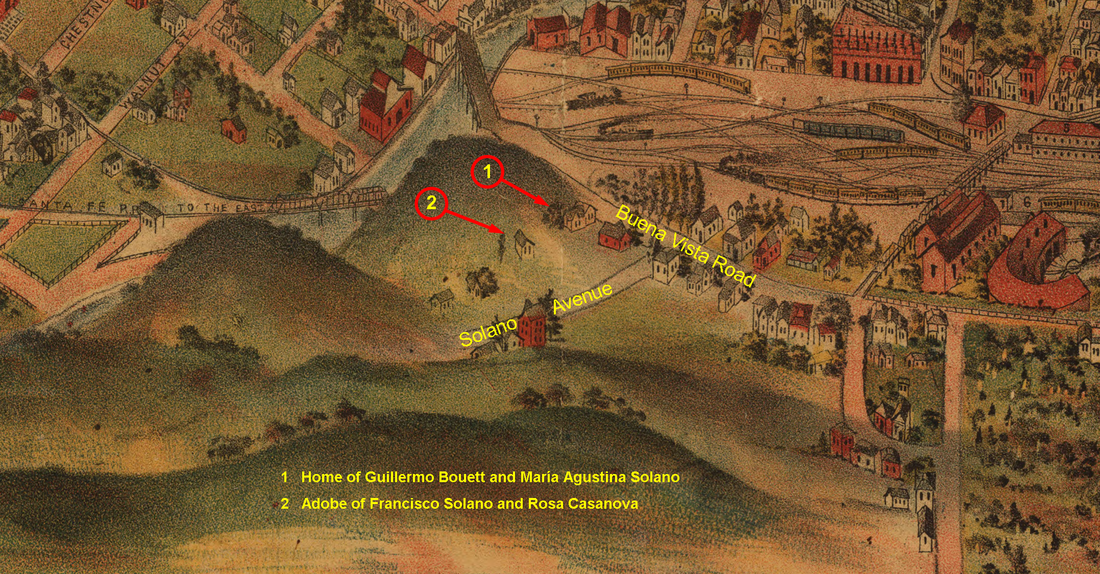

Part 2 of this blog will describe the water wheel in greater detail and pinpoint its location, on both historic maps and a satellite image of the area today. A bird's eye view of Solano Canyon from 1891 The bird's eye view map is a cartographic genre all its own. While they are, indeed, maps, bird's eye views can also be works of art. Their accuracy as maps may be questionable and their value thereby limited, but still ... The second image, below, is but a very small small portion of a large, bird's eye view map of Los Angeles by the San Francisco publisher H. B. Elliott, published in 1891. The original map is huge — 31.9" x 45.3" — and the detail is incredible. This is the original map: Notice that the actual map portion of the whole — the bird's eye view — occupies only about 50% of the total map area. The border is a series of views of 24 buildings, one house, and the interiors of a grocery store and the Chamber of Commerce. But it is that very small area of the map that is of interest here. If we zoom into Solano Canyon, we find some interesting detail. The question, of course, is whether what we are seeing is accurate. The area is readily recognizable: notice the railroad yard with its roundhouse, and Buena Vista Road and Solano Avenue (annotated), the Santa Fe Railroad bridge across the Los Angeles River, and the Buena Vista bridge across the river, as well.

Now look at the annotations numbered 1 and 2. While it is, admittedly, merely speculation and with no assurance of accuracy, it is entirely possible that #1 is the home of María Agustina Solano and her husband, Guillermo Bouett at 1425 Buena Vista Road, and that #2 is the location of the original adobe that was built between 1866 and 1871 by founder Francisco Solano for his wife, Rosa Casanova, and their family. María Agustina Solano, of course, is the daughter of Francisco Solano and Rosa Casanova, and for whom, Bouett Street in Solano Canyon is named. It is known with certainty from other maps, rigorously surveyed and drawn to scale (primarily by Francisco and Rosa's son, Alfredo Solano), that location #2 is the relative location of the adobe, and it is also known with certainty that María Solano and Guillermo Bouett built a house on Lot #100 of the original Solano Tract after 1888 and before 1900, which is located at the corner of (now) North Broadway and Casanova Street. So are we seeing a view from history on this map? One doesn't know for sure, but it surely seems possible. |

About the AuthorLawrence Bouett is a retired research scientist and registered professional engineer who now conducts historical and genealogical research full-time. A ninth-generation Californian, his primary historical research interests are Los Angeles in general and the Stone Quarry Hills in particular. His ancestors arrived in California with Portolá in 1769 and came to Los Angeles from Mission San Gabriel with the pobladores on September 4, 1781. Lawrence Bouett may be contacted directly here.

Archives

July 2018

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed