|

Los Angeles, California, 1900. The Twelfth United States Census, taken on June 1, 1900, revealed that there were 104,703 people living in the City of Los Angeles, with an additional 70,000 or so living outside the City in the county. Of the nearly 105,000 residents of the City, slightly more than 32,000 of them were children under the age of 18 --in other words, children of school age.

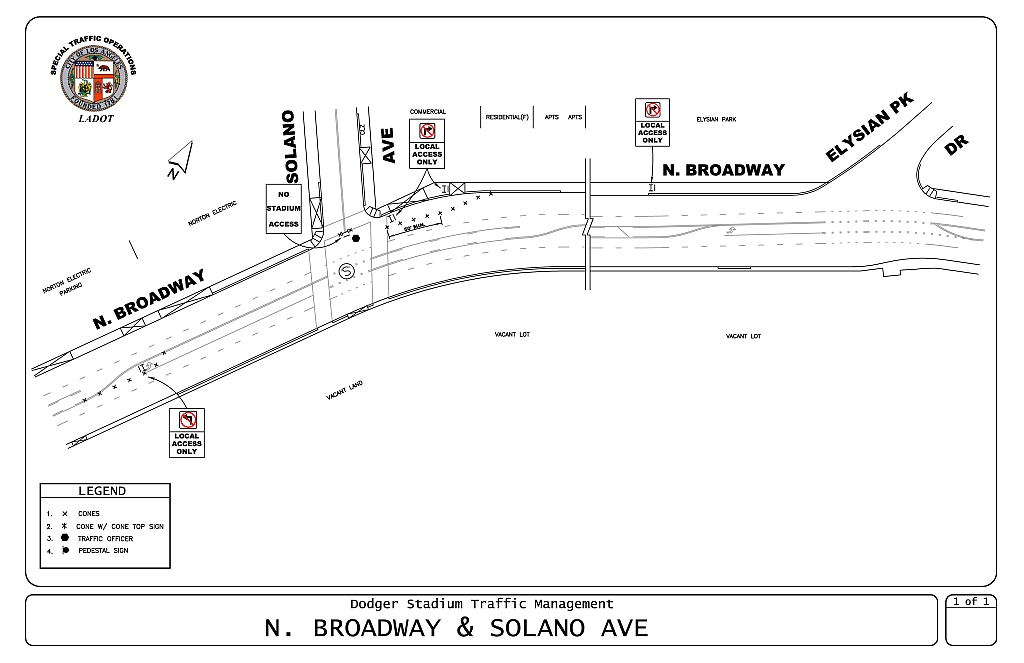

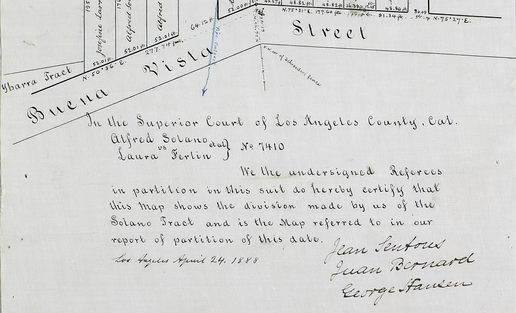

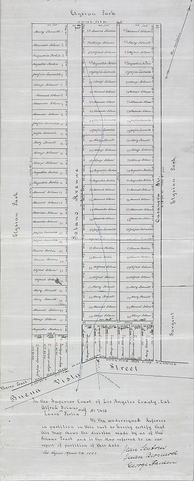

The Solano Canyon community grows

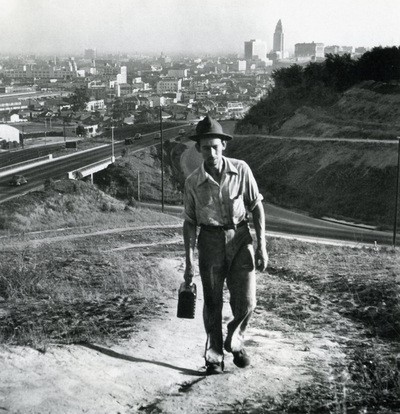

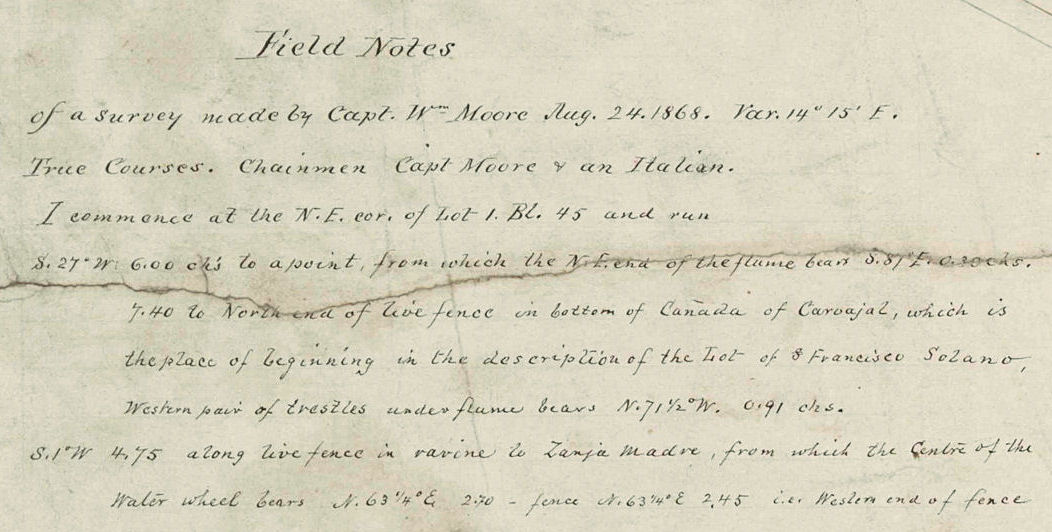

By 1900, Solano Canyon was home to 52 families: 8 lived on Buena Vista Road (now North Broadway), 10 lived on Casanova Street, and 34 lived on Solano Avenue, for a total of 196 people. As many as 80 of these were children, many of whom were of school age. The first home in the la Loma community was not built until 1909, a 12' x 12', one-room house at 814 Spruce Street built by John Radulovich.

A school bond election passes

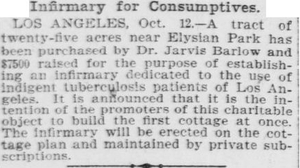

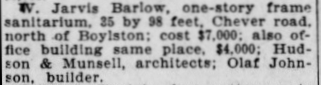

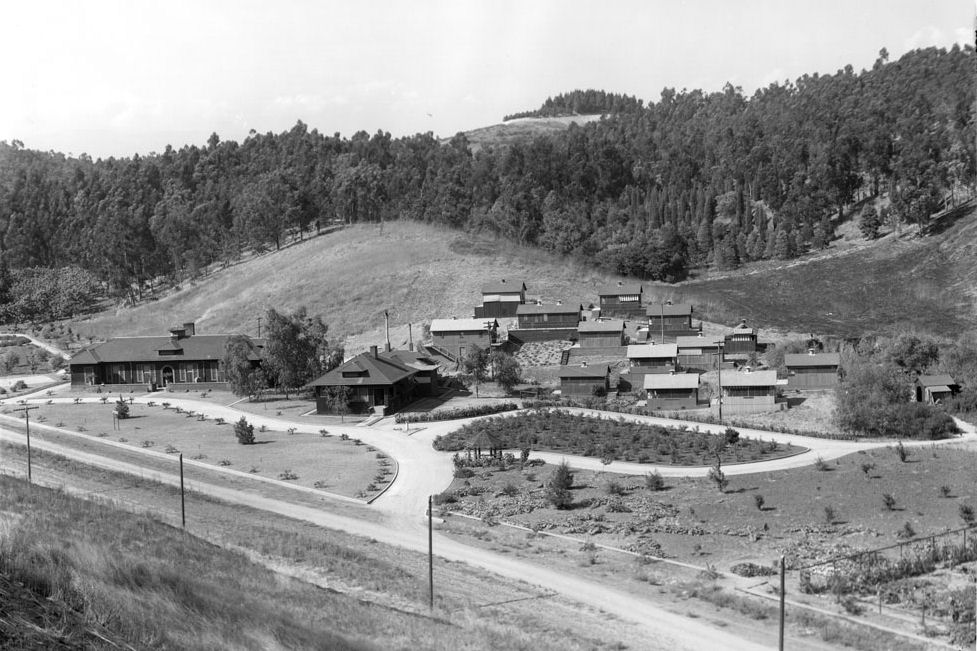

By 1903, Los Angeles City schools were being described as "... fearfully crowded ...". Early that year, a bond election was held in Los Angeles, the purpose of which was to sell bonds to pay for construction of new schools within the City. The bond issue passed easily, and as a result of the election, at its meeting of April 21, 1903, the Building Committee of the City Council met and awarded contracts for the architectural design and construction of 18 new elementary schools, a Polytechnic High School, and a warehouse. It was the largest amount of money ever awarded for construction of schools in Los Angeles' history: $476,625, slightly less than half of which ($200,000) was allocated for the new Polytechnic High School alone. The new Solano Avenue School was one of the smaller schools in the group, at four rooms plus some site work, and the value of the contract was $12,500. The architectural contract was let to the firm of Hudson & Mansell, a Los Angeles architectural firm that a year earlier had donated its services to draw up the plans for the new Barlow Sanatorium on Chavez Ravine Road.

Solano Canyon gets its own school

It is not known with certainty when the new Solano Avenue elementary school first opened its doors to students, but it must have been during the 1903-1904 school year or possibly the year after that, because the Board of Education, at its regular meeting held January 25, 1904, assigned Miss Addie J. Samuels, then a teacher at the Swain Street School, as teacher at the new Solano Avenue School and named her principal as well.

Addie J. Samuels was a long-time teacher and principal in Los Angeles. She was an active teacher from at least 1885, and she came to Los Angeles for the 1892-93 school year as a 3rd- and 4th-grade teacher at the Swain Street School, located on the corner of N. Griffith Avenue, where she remained until her assignment to the Solano Avenue School in 1903. In 1906-07, she was named principal at the Breed Street School, where she remained at least through the 1910-11 school year, and as late as 1918, she was the principal of the Sixty-eighth Street School at 714 Iola St., in a career that spanned more than 33 years.

At a special session of the Board of Education held August 22, 1904, it was announced that the 1904-05 school year would begin on Monday, September 25, 1904. Miss Mary L. Small, a teacher in Los Angeles since 1893, and Miss Clara E. Heald were assigned as teachers at Solano elementary, with Addie J. Samuels remaining as principal.

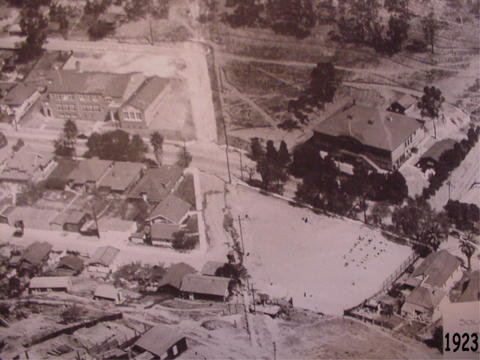

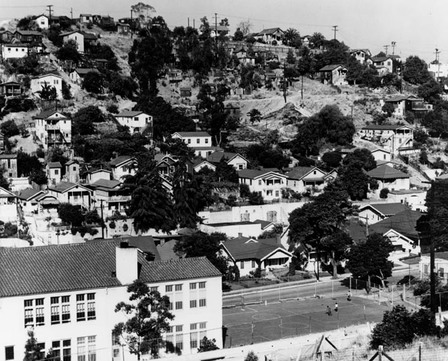

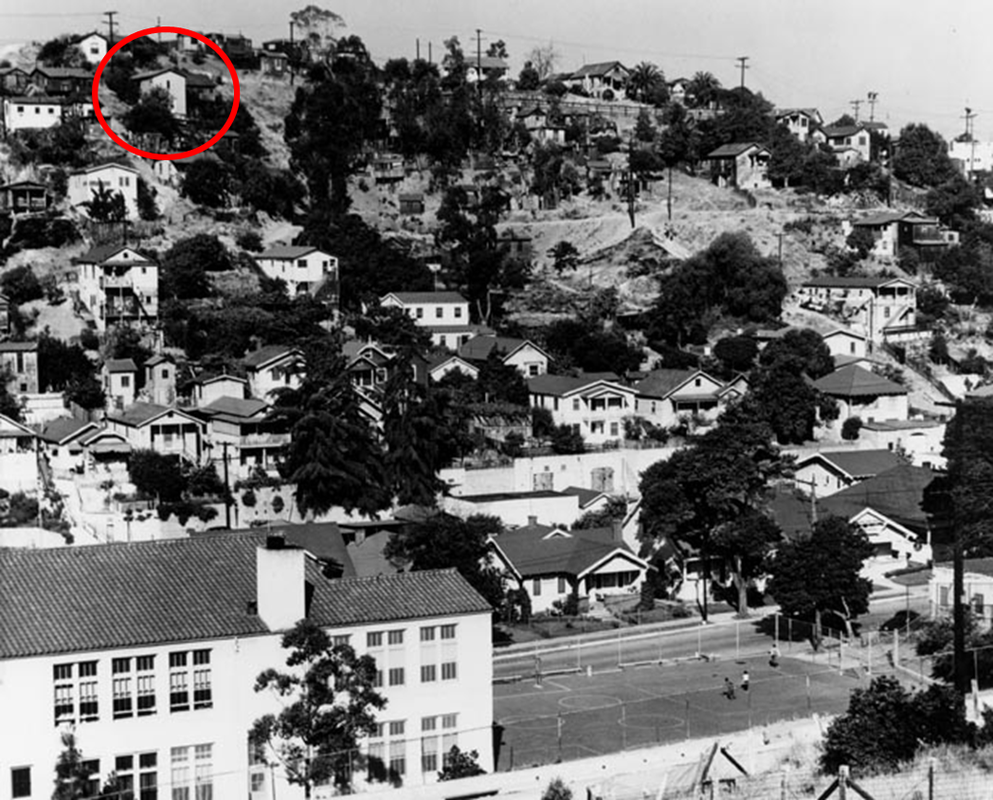

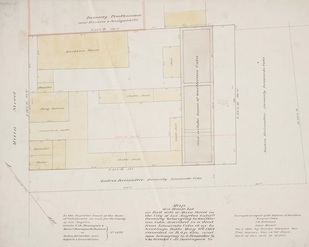

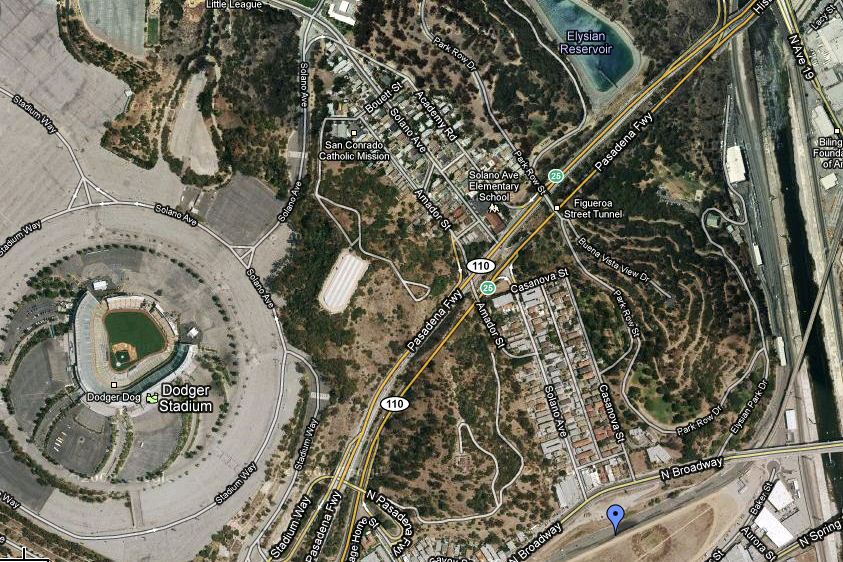

In the photograph above, the original Solano Avenue school is the large building on the right, facing Solano Avenue. The vacant lot across the street served as the playground for the school. Across Yuba Street to the left is the new Solano Avenue school, which is the current school. Also identified in this photograph are Casanova Street (top) and Amador Street (bottom), with Solano Avenue running roughly horizontally through the middle of the photograph.

The original school is torn down

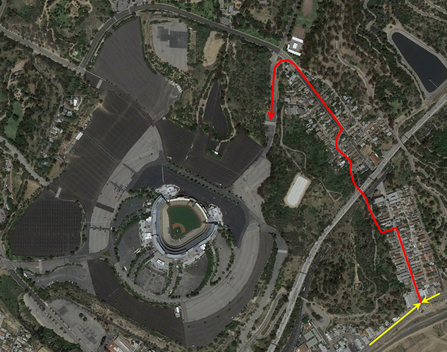

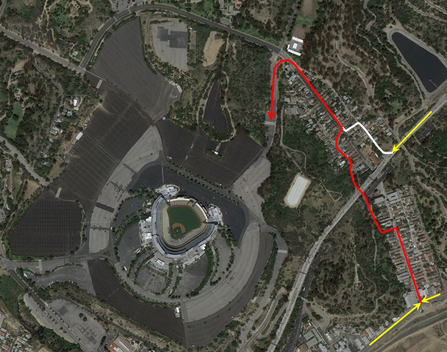

The original Solano Avenue school was eventually replaced by the new school shown in the photograph above and was torn down in 1935 as part of the construction of the Pasadena Freeway, now CA-110. Parts of the foundation, a retaining wall and the concrete stairs leading up to the school remain, however, as the retaining wall of, and entrance to, the five-acre Solano Community Garden.

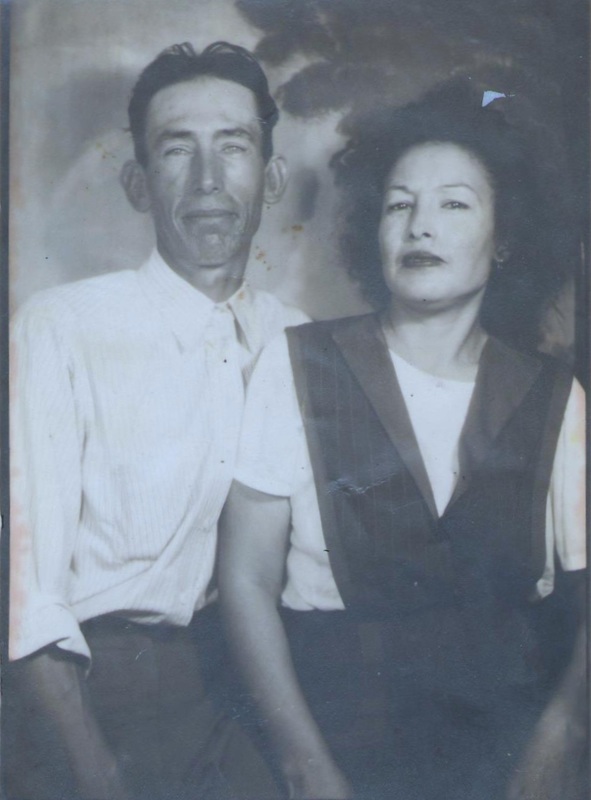

A personal connection to the school

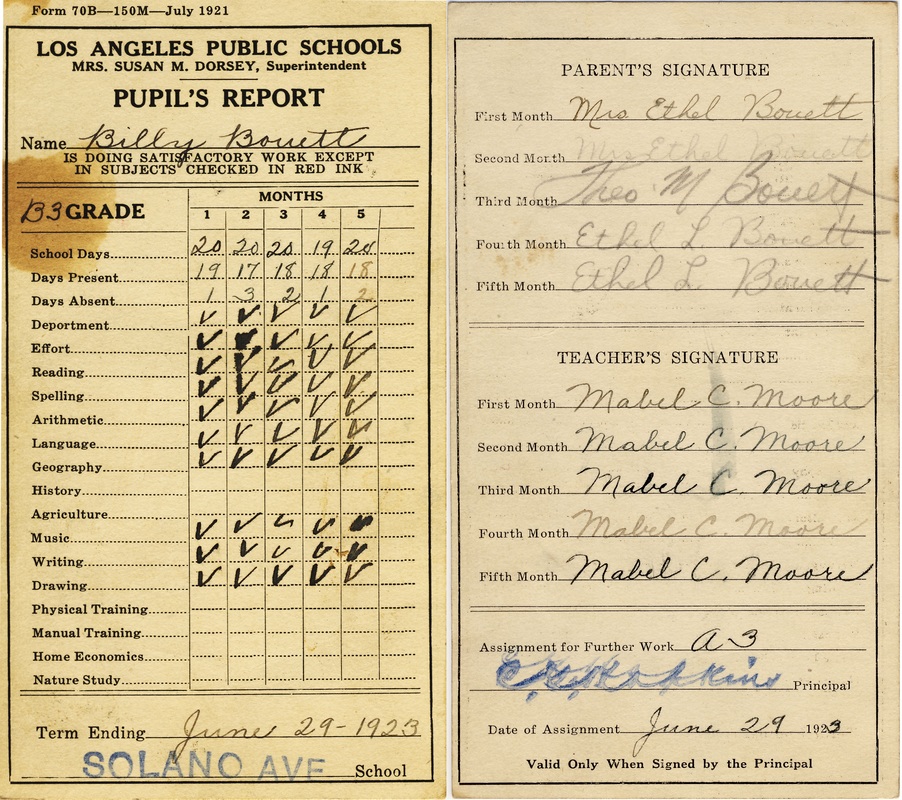

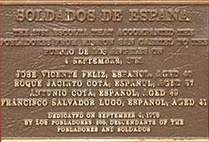

In 1903, when the original Solano Avenue school was built, the author's grandfather, Teodoro Manuel Bouett, grandson of Solano Canyon founders Francisco Solano and Rosa Casanova, was living with his parents, Maria Agustina Solano and Guillermo Bouett, and his four surviving siblings at 1425 Buena Vista Road, now North Broadway, on the corner of Buena Vista Road and Casanova Street. He was eight years old. After the new Solano Avenue school opened, Teodoro Bouett became a student there. Then, in 1920, my father, Guillermo Carlos Bouett, son of Teodoro, became the second generation of his family to attend the Solano Avenue school.

Guillermo Bouett attended Solano elementary between September 1920 and June 1926, from the 1st through the 6th grades. The following table lists his teachers and principals during that time, compiled from his original report cards. In addition, other known teachers and principals are listed, along with their dates of service.

|

About the AuthorLawrence Bouett is a retired research scientist and registered professional engineer who now conducts historical and genealogical research full-time. A ninth-generation Californian, his primary historical research interests are Los Angeles in general and the Stone Quarry Hills in particular. His ancestors arrived in California with Portolá in 1769 and came to Los Angeles from Mission San Gabriel with the pobladores on September 4, 1781. Lawrence Bouett may be contacted directly here.

Archives

July 2018

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed